When you hear “acidity” in coffee, you might think of sourness or stomach woes, but it’s actually a star player in a great cup. Acidity brings a bright, tangy zip that lifts the flavor, balancing sweetness and body. It’s not about pH—coffee’s slightly acidic at 4.9–5.5, milder than orange juice (3.3–4.2)—but about how organic acids dance on your tongue. From citric zing to malic crispness, acidity shapes your brew’s personality.

In this guide, we’ll unpack what coffee acidity is, the acids behind it, how it affects taste, and where the most vibrant coffees come from. Whether you love a tart kick or prefer low-acid sips, you’ll learn how to pick and brew your perfect cup. Let’s dive in.

What Is Acidity in Coffee?

Acidity in coffee is the lively, tangy sensation you taste, often described as bright, tart, or crisp. It’s not the coffee’s pH but the flavor from organic acids in the beans, like citric or malic, that create a sour-sweet spark. These acids, over 30 in total, make up 1–2% of a bean’s weight and define its character, per 2024 coffee chemistry studies. Think of acidity as the high notes in a song—too much can overwhelm, too little feels flat.

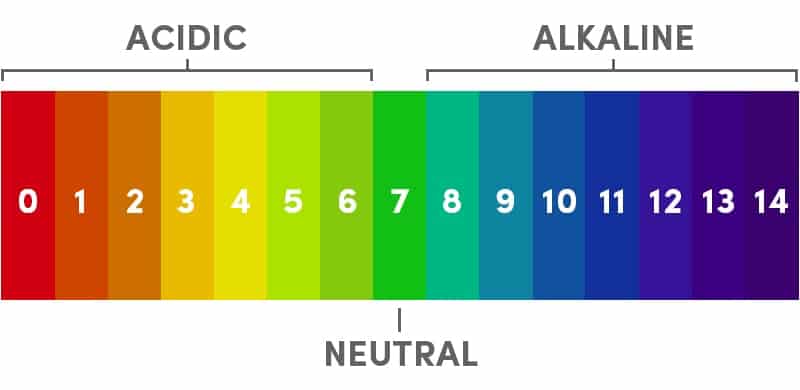

Coffee’s acidity is milder than many drinks—soda (pH 2.5–3.5) or beer (pH 4.0–4.5)—so it’s gentle for most. But if acidity bugs your stomach, low-acid options exist, as we’ll cover. The key is balancing “good” acids (bright, flavorful) with “bad” ones (bitter, harsh), shaped by bean type, roast, and brewing.

Is Coffee Acidity Harmful?

Nope, coffee acidity isn’t harmful for most people. Its pH (4.9–5.5) is less acidic than orange juice or soda, and organic acids like citric add health perks, like antioxidants, per 2025 health blogs. However, chlorogenic acids (CGAs), which make up 5–10% of beans, can irritate sensitive stomachs, especially in dark roasts where CGAs break into quinic acid, adding bitterness. If acidity causes discomfort, try low-acid coffees (e.g., Brazilian, Sumatran) or cold brew, which extracts less quinic acid.

Moldy beans, rare with proper storage, are the only real health risk—toss any with a musty smell or white patches. Otherwise, acidity is a flavor feature, not a flaw, and you can tweak brewing or bean choice to suit your gut.

The Acids Behind Coffee’s Flavor

Coffee’s acidity comes from organic acids and CGAs, each adding unique notes. Organic acids are the “good” ones, delivering brightness, while CGAs contribute body and, if overdone, bitterness. The table below breaks down the main players:

| Acid | Flavor Profile | Found In |

|---|---|---|

| Citric | Bright, citrusy (lemon, orange) | Citrus fruits, Colombian coffee |

| Malic | Crisp, smooth (green apple) | Apples, Kenyan coffee |

| Tartaric | Sweet, fruity (grape, banana) | Grapes, Ethiopian coffee |

| Acetic | Wine-like, bright (vinegary in excess) | Vinegar, Costa Rican coffee |

| Chlorogenic (CGA) | Body, slight bitterness (quinic in dark roasts) | All coffee, higher in dark roasts |

Organic acids shine in light roasts, adding zest, while CGAs, broken down in dark roasts, can turn bitter. Roasters aim to maximize organic acids and manage CGAs for balance, per SCA guidelines.

Why Are Some Coffees More Acidic?

Ever wonder why some coffees zing with tartness while others feel smooth? The answer lies in a mix of bean type, growing conditions, and how the coffee’s made, all shaping its acid profile. From the variety of the bean to the altitude it’s grown at, these factors decide whether your cup pops with brightness or leans mellow, giving you endless options to match your taste.

- Bean Type: Arabica beans, common in specialty coffee, have more organic acids than Robusta, which is less acidic but bitter. Varieties like Typica (Central America) are brighter than Catimor (Asia).

- Growing Conditions: High-altitude (1000–2000m), cooler climates (e.g., Kenya’s Nyeri, Ethiopia’s Yirgacheffe) slow bean maturation, boosting acids like citric and malic. Volcanic soils (e.g., Kona, Costa Rica) and wet processing (washed) enhance acidity, per 2025 roaster data.

- Roast Level: Light roasts (e.g., City roast) preserve organic acids, tasting tart. Dark roasts (e.g., French roast) degrade acids into quinic compounds, lowering acidity but adding bitterness.

- Brewing Method: Pour-over and espresso highlight acidity by extracting acids quickly, while drip or cold brew mellows it, per brewing studies. Water at 195–205°F extracts acids optimally; too hot (210°F+) pulls bitter CGAs.

- Processing: Wet-processed coffees (Central America) retain more acidity than dry-processed (Ethiopia), which emphasize sweetness.

- Bean Age: Fresh beans (roasted within 1–2 months) retain vibrant acids; stale beans lose them, tasting flat.

How Roasting Shapes Acidity

Roasting is where coffee’s flavor gets fine-tuned, especially its acidity. The way beans are heated can dial up those bright, tangy notes or mellow them out, depending on the roast level. By controlling temperature and time, roasters bring out the best in a bean’s natural acids, creating everything from zesty light roasts to smoky dark ones.

Roasting transforms a bean’s acid profile. Green beans are packed with organic acids and CGAs, but heat alters their balance. Light roasts (375–400°F) preserve citric and malic acids, giving a zesty, floral cup, ideal for Ethiopian or Kenyan beans. Medium roasts (400–430°F) balance acids with sweetness, suiting Colombian coffees. Dark roasts (430–450°F) break CGAs into quinic acid, reducing brightness and adding a roasted, smoky edge, common in Brazilian or Sumatran blends.

Skilled roasters avoid over-roasting to prevent bitterness, but dark roasts suit low-acid preferences. If acidity bothers you, go for dark roasts or low-acid origins, per X users praising Sumatran blends in 2025.

Brewing for Acidity Control

Your brewing setup can make or break how acidic your coffee tastes. From grind size to water temperature, small tweaks let you highlight or tame those tangy flavors to match your vibe. Whether you’re using a pour-over or a French press, these choices shape the balance of brightness in every sip.

- Grind Size: Medium-coarse grinds (like sea salt) for pour-over or French press bring out organic acids without bitterness. Fine grinds (espresso) speed extraction, amplifying CGAs.

- Water Temperature: Stick to 195–205°F, per SCA. Use a gooseneck kettle with a thermometer or let boiled water (212°F) cool 30 seconds. Too hot extracts bitter acids; too cool mutes brightness.

- Brew Time: Short brews (2–3 minutes, pour-over) emphasize acidity; longer brews (4–5 minutes, immersion) balance it with body. Cold brew (12–24 hours) cuts acidity for smoother sips.

- Method: Try pour-over (Hario V60) for bright notes or cold brew for low-acid ease. Espresso lovers, expect a tart kick.

Experiment to find your sweet spot—start with a medium-coarse grind, 200°F water, and 3-minute pour-over, then adjust.

Where Do the Most Acidic Coffees Come From?

The world’s brightest, most acidic coffees hail from specific corners of the globe. High-altitude regions with cool climates produce beans packed with zesty acids, and we’ll tour the top spots. These areas, from Hawaii to Ethiopia, grow coffees that light up your palate with vibrant flavors.

- Kona, Hawaii: Grown on volcanic Mauna Loa slopes (600–1800m), Kona’s light roasts burst with citric and malic notes. Rare and pricey, per 2025 market data.

- Costa Rica: High-altitude Tarrazú (1200–1900m) and organic farms yield acetic and citric-heavy coffees, often wet-processed for clarity.

- Colombia: Andean Nariño beans (1500–2000m) shine with citric zing, balanced by caramel sweetness in medium roasts.

- Kenya: Nyeri’s White Highlands (1700–2000m) produce citric and malic-rich coffees, with sparkling acidity, per roaster reviews.

- Ethiopia: Yirgacheffe (1800–2200m) offers tartaric and floral notes, often dry-processed for fruitiness, lauded in 2025 X posts.

- Jamaica: Blue Mountain (1000–1700m) blends citric and malic acids for a smooth, pricey cup, popular in Japan.

Low-acid options? Try Brazilian Cerrado or Sumatran Mandheling, grown at lower altitudes (800–1200m) with dry processing, yielding earthy, less tart flavors.

Tips for Enjoying Coffee Acidity

Whether you’re all about that tart kick or prefer a smoother sip, you can tailor your coffee experience. These practical tips will help you pick, brew, and savor coffee with just the right acidity. From choosing beans to tweaking your setup, here’s how to make acidity work for you.

- Pick Your Origin: Love brightness? Go for Kenyan or Ethiopian light roasts. Want mellow? Try Brazilian dark roasts.

- Check Roast Date: Buy beans roasted within 1–2 months for vibrant acids, per specialty roasters like Counter Culture.

- Store Right: Keep beans in an airtight canister, cool (50–70°F), and dark to preserve acids. Avoid fridges (moisture risk).

- Experiment: Tweak grind, temperature, or brew time to dial in acidity. A Hario V60 with 200°F water highlights tart notes.

- Cold Brew Option: If acidity’s too much, cold brew softens it without losing flavor.

- Fresh Brews: Drink coffee within 30 minutes of brewing—sitting on a hot plate turns it bitter, masking good acids.

Final Thoughts

Coffee acidity isn’t a villain—it’s the spark that makes your cup sing. From citric zing to malic crispness, organic acids add life, while roasts and brewing let you control the vibe. High-altitude gems like Kenyan or Yirgacheffe bring the brightest flavors, but low-acid Brazilian blends have their fans too. Experiment with beans, grinds, and methods to find your groove. Got a favorite acidic coffee? Share it in the comments and keep chasing that perfect brew!